Software teams are increasingly relying on large language models to plan, write, and refactor code. The promise is attractive: describe what you want in natural language and get working software back. The reality is more complicated. Model output quality is inconsistent, costs add up quickly, and moving from a nice-looking prototype to a reliable product often requires more human effort than expected.

Race Mode is designed to address this gap. It is not a new model. It is a way of using multiple models and agents in parallel, then selecting a single, solid outcome instead of gambling on the first draft.

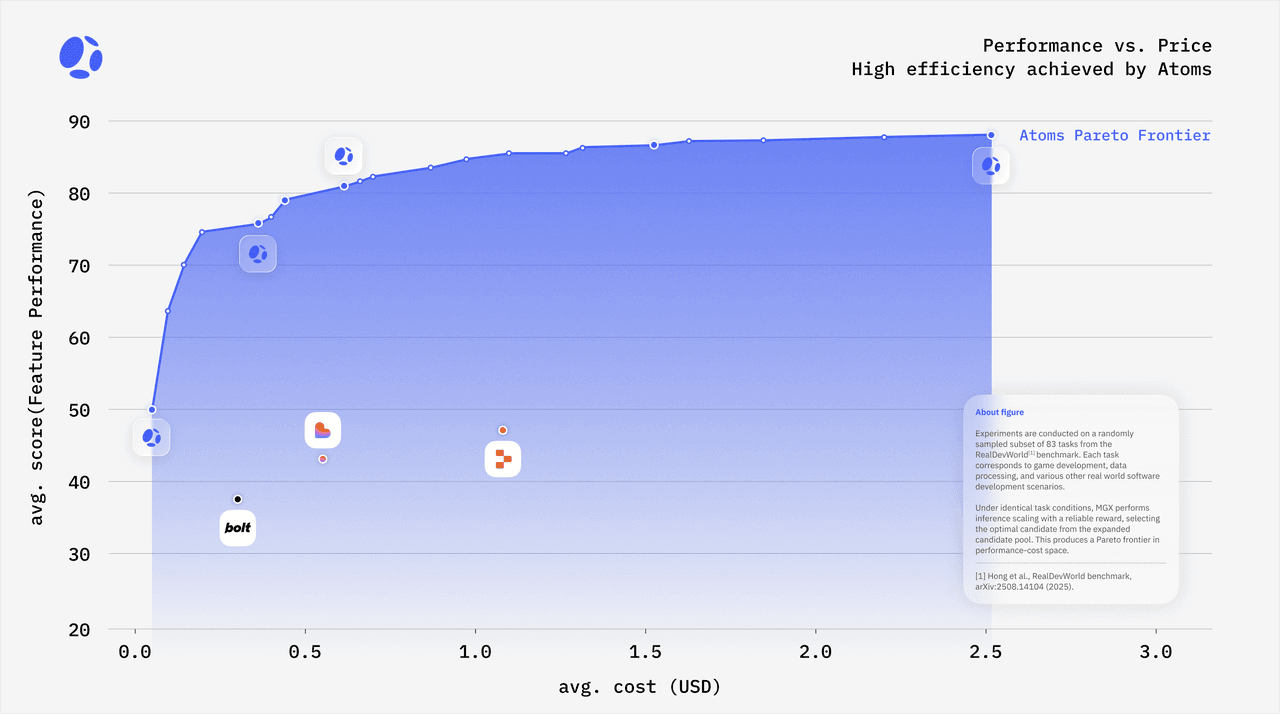

From our internal benchmark on RealDevWorld, a suite of 194 production-style software projects, this best-of-N approach increased effective pass rates from 0.30 to 0.85 on challenging tasks, while allowing us to operate along a Pareto frontier where we can reach a given quality level at up to 80% lower cost compared to running strong proprietary models alone. The same method delivers solutions that, in practice, we measure to be around 45% better than top single-model setups at comparable budgets.

The goal is to be concrete and transparent about what works, what doesn’t, and where the trade-offs are.

1. Why Single-Model AI Development Falls Short

Most AI-assisted developments today follow the same pattern:

- You describe a feature or change.

- A single model generates a plan or code.

- You inspect the result, then either accept it, request changes, or regenerate it.

This process is similar across tools, whether you are using an IDE extension, a chat-based coding assistant, or an AI-driven cloud environment.

There are three structural problems with this pattern.

1.1 Output Quality Is Noisy By Design

Large language models are probabilistic. For non-trivial development tasks, there is no single “correct” answer; there are many possible implementations of varying quality. With a single model call:

- Two prompts with minor rephrasing can produce very different results.

- Re-running the same prompt can swing between excellent and unusable code.

- Longer, multi-step tasks accumulate minor errors until the final result is fragile.

The research community has openly documented these issues. For example, work on self-consistency and best-of-N sampling shows that sampling multiple outputs and selecting the best can significantly improve reliability on reasoning and coding tasks (OpenAI Reasoning Guide) compared to using a single sample from the model distribution. Yet most developer tools still expose only a single “generate” button.

1.2 Cost And Quality Trade Off In Opaque Ways

Developers are increasingly aware of per-token pricing and model tiers. Stronger models cost more but are not uniformly better across all tasks. Open benchmarks such as HELM and Open LLM Leaderboard show a wide variation in performance across tasks and domains.

In practice, this means:

- Using only the strongest proprietary model is often overkill and expensive.

- Using only cheaper or open models can save money, but increases debugging time and failure rates.

- Manually deciding which model to use for each request does not scale beyond a small group of expert users.

1.3 Prototypes Are Easy; Production Systems Are Not

Most AI tools are good at generating code snippets or UI prototypes. The difficult part is turning these snippets into an application that:

- Has a consistent architecture,

- Persists data correctly,

- Handles authentication and payments,

- Survives real users.

Going from a nice “demo video” to a service that can plausibly sustain revenue still requires substantial engineering.

Race Mode resides within Atoms, which already encompasses the full stack: research, product planning, architecture, UI, backend, data, and deployment. Race Mode narrows its focus to a specific question: Given the same task, can we utilize multiple models and agents in parallel to consistently produce a better full-stack solution at a more reasonable cost?

2. What Race Mode Is

Race Mode is a best-of-N execution layer for Atoms. When enabled for a task, Atoms does not rely on a single agent chain or a single model configuration. Instead, it orchestrates several independent “teams” in parallel and then helps you choose one outcome.

It is important to clarify what Race Mode is not:

- It is not an extra model.

- It is not a simple “regenerate multiple times” button.

- It is not an A/B testing tool where you manually compare random drafts.

Race Mode is a structured, benchmark-driven way of:

- Selecting a small set of model configurations that are promising for a given budget.

- Running them in parallel through full agent workflows.

- Scoring and ranking the resulting solutions, using both automated metrics and runtime signals.

- Presenting the best candidates in a focused interface, so you can pick one plan and continue development without being buried in noise.

This process is built on two ideas that are already well-established in research and industry:

- Best-of-N sampling and ensembling as a way to improve model performance.

- Pareto-optimal frontier analysis to balance cost and quality.

We simply apply them to real software projects instead of synthetic puzzles.

3. The Benchmarks Behind Race Mode

Before introducing Race Mode to users, we needed to determine if it actually improves outcomes on realistic tasks, rather than cherry-picked examples.

3.1 RealDevWorld: 194 production-style projects

Our primary evaluation ground is RealDevWorld, a benchmark suite of 194 production-style software projects. Each project encodes requirements, structure, and constraints closer to what a small team or founder would actually build.

In this benchmark, we first evaluated “single path” generation, where one agent team, one model configuration, and one attempt are used per project. On a subset of particularly challenging tasks, this setup achieved a success metric of around 0.30. Concretely, this means:

- Many projects produced code that compiled and ran partially but failed on important behaviors.

- Some flows stalled on planning or lost context mid-way.

- The reliability was not where we wanted it to be for building real applications.

3.2 From 0.30 to 0.85 With Best-Of-N

We then evaluated a Race Mode pipeline on the same task set:

- For each project, we ran multiple parallel agent teams.

- These teams used different models and configurations, chosen based on previous experiments.

- We scored the outputs using task-specific checks and runtime signals.

With this setup, the effective success metric on the difficult subset increased from 0.30 to 0.85. The difference came from both:

- The diversity of solutions: different models make different mistakes.

- The ability to automatically discard obviously failing paths and surface the robust ones.

Best-of-N improvements of this kind are consistent with external work. For example:

- Google DeepMind reports similar gains when applying best-of-N and verification to mathematical reasoning (arXiv).

- Anthropic describes how sampling multiple candidate chains and selecting those that pass consistency checks improves reliability in Claude-based systems (Anthropic Docs).

Race Mode adapts these ideas to full-stack software tasks.

3.3 The Cost–Quality Frontier

Running multiple teams in parallel incurs higher costs per request than a single attempt. The question is whether the total cost per successful project increases or decreases.

To answer this, we treated each combination of models and configuration as a point on a cost vs. quality plane:

- The x-axis is the average normalized inference cost (tokens × price), plotted on a log scale to make significant cost differences comparable on the same chart.

- The y-axis is average performance score on RealDevWorld.

We then determined the Pareto frontier, which is the set of configurations where it is impossible to improve quality without increasing cost, or reduce cost without compromising quality. This is a standard technique in optimization (MIT News).

Two observations from this analysis:

- Many naive approaches—“always use the strongest proprietary model” or “always only use the cheapest model”—fall significantly short of the optimal point. They are either more costly than necessary for the quality provided, or they sacrifice too much reliability to save a small amount.

- Carefully designed Race Mode configurations, which mix open and proprietary models and limit N to a small number of strong candidates, land on or near the Pareto frontier.

In practical terms, this gives us room to operate in regimes where:

- For a fixed budget, Race Mode yields around 45% higher effective quality than single-model setups we tested.

- For a fixed quality threshold, Race Mode configurations run at up to 80% lower inference cost than “just use the strongest model for everything.”

These numbers follow naturally from treating model choice and ensemble size as an optimization problem, rather than relying on guesswork.

4. How Race Mode Works in Practice

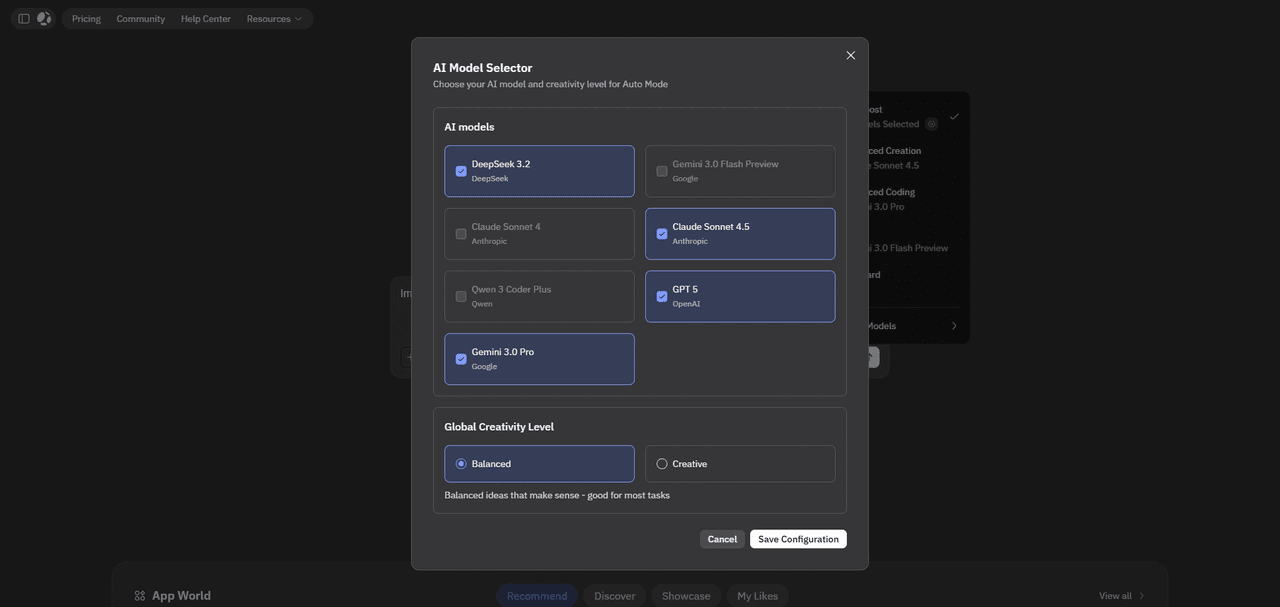

From the user’s perspective, Race Mode is a single toggle in the Atoms interface. Underneath, several layers work together.

4.1 Activating Race Mode

Race Mode is available on Atoms plans with sufficient compute and storage allocation. When you enable it for a chat:

- The model selector switches to an Auto mode labeled as designed for Race Mode.

- You can optionally open an advanced configuration dialog to see and adjust:

- Which models participate in the race (e.g., a mix of open and proprietary models).

- The maximum number of teams (up to four).

- Temperature ranges or other sampling parameters.

In most cases, you can leave these defaults alone. They are derived from our Pareto-frontier analysis and RealDevWorld experiments, rather than from arbitrary presets.

4.2 Parallel Teams, Not Parallel Snippets

When you submit a task with Race Mode enabled, Atoms spins up several child chats in the background. Each child chat corresponds to a separate “team”:

- It has its own planning steps.

- It uses a specific model or model mixture.

- It goes through the full lifecycle for the request: research (if enabled), product breakdown, architecture, implementation, and basic validation.

This is a critical distinction. Race Mode does not sample multiple completions for a single API call. It is running several full workflows in parallel, with different agents and models making independent decisions.

During this time:

- The input box is disabled to avoid interference.

- A status bar indicates the number of teams running and the number that have finished.

- You can open a team to follow its progress, but you cannot edit code directly until the race ends or you explicitly stop it.

4.3 Scoring and Ranking Candidate Solutions

As teams complete their work, Atoms collects signals to estimate the quality of each solution:

- Structural checks: Does the generated project build? Are dependencies coherent?

- Runtime checks: Do basic tests pass? Does the generated app run without immediate critical errors?

- Heuristic metrics: Complexity, duplication, and adherence to the task description.

- Embedding-based similarities between the requested behavior and the produced code paths.

This is not a perfect oracle. No automated scoring will capture every nuance of a product idea. The goal is more modest: to separate clearly broken attempts from promising ones and to highlight the latter for your review.

This approach is aligned with broader trends in LLM verification and evaluation. For independent reading:

- “Measuring Coding Performance for LLMs” – GitHub Copilot team (GitHub Blog) discusses evaluating coding assistants using test-based metrics.

- “AgentBench: Evaluating LLMs as Agents” (arXiv) explores task-based evaluation for agent systems.

Race Mode’s scoring uses similar principles but is tuned for Atoms’ full-stack outputs.

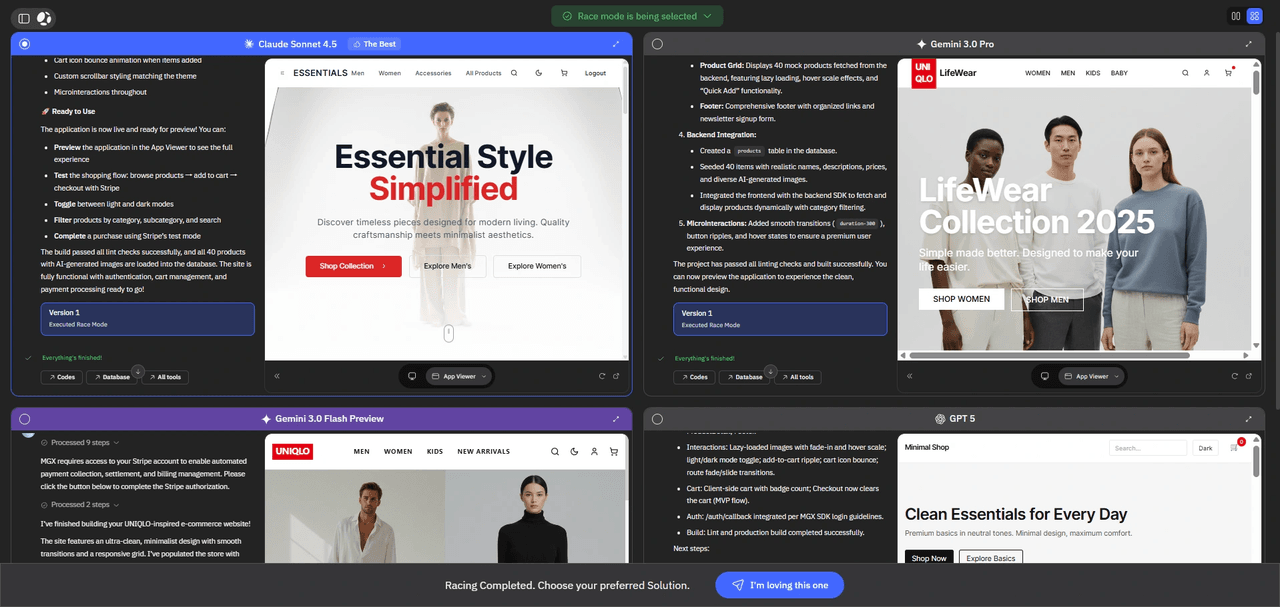

4.4 Presenting Results Without Overwhelming You

Once Race Mode finishes (or you stop it manually), the interface switches from execution to selection.

You see a small set of candidate solutions—typically up to four—each represented as a window with:

- The model or configuration that produced it.

- A concise summary of what it built.

- A visual preview of the application where applicable.

- Access to the underlying code and project structure.

Interaction is deliberately staged to reduce accidental actions:

- First click on a window only focuses it. The header changes to indicate selection.

- A second click on the explicit action button—“View details”, then “I’m loving this one”—accepts that solution.

When you accept a solution:

- Atoms brings it back into the main chat as the new baseline project.

- Other candidate projects are cleared from your workspace to avoid confusion and storage waste.

- The system posts a summary message, including the internal score and the model chosen, so there is a traceable record of what happened.

If all teams fail to reach a satisfactory state, you still see their partial outputs. You can choose one to continue working from or abort the race entirely. In that case, Atoms switches you back to the default mode with a plain explanation of what went wrong (credits, resource limits, or internal errors).

5. Where Race Mode Fits in Atoms’ Full-Stack Workflow

Atoms is built around the idea of an AI team: a researcher, product manager, architect, engineer, data analyst, and team lead working together through a chat interface. These agents already handle:

- Deep research on markets and competitors (through our DeepResearch pipeline, which scores 73% on the Xbench-DeepResearch benchmark (arXiv); for context on this benchmark style.

- Product specification and user journey mapping.

- System and data architecture.

- Frontend and backend implementation (user authentication, database schemas, payment flows).

- Deployment to a runnable application environment.

Race Mode does not replace this pipeline. It wraps around parts of it in situations where a single attempt is not reliable enough.

Some typical use cases:

5.1 First Serious Implementation Of A New Product

When you move from a vague idea to the first “serious” implementation, something you expect to demo to customers or investors. And Race Mode helps avoid the situation where you pick an unlucky draft.

Instead of:

- One attempt that produces a brittle backend or confused data model,

You get:

- Several competing implementations, all aligned with the same specification, but built with different architectural and modeling decisions.

This is often where the 0.30 vs. 0.85 difference on RealDevWorld becomes visible. A few failing attempts matter less if one solid option completes the job.

5.2 Complex Refactors Or Migrations

Race Mode is also useful when you ask Atoms to perform a non-trivial change to an existing project:

- Moving from a monolithic backend to a service-oriented layout.

- Changing the data schema in ways that touch many components.

- Introducing new payment providers or authentication flows.

In these scenarios, subtle mistakes can break the system. Running multiple teams reduces the chance that the only attempt you see is the one that missed a crucial dependency or edge case.

5.3 Exploring Design Variants Under Budget Constraints

Because Race Mode configurations are grounded in Pareto analysis, you can treat them as knobs: if you increase N or include stronger models, you move along the frontier. If you restrict N and rely more on efficient models, you slide towards the cheaper side.

This allows you to:

- Use more aggressive Race Mode settings for critical features.

- Use conservative settings, or no race at all, for quick internal tools.

The underlying principle—finding efficient points on a cost–quality frontier—is the same idea used in multi-objective optimization (see a gentle introduction from the University of Massachusetts Amherst).

6. Practical Considerations and Limitations

It is essential to be clear about what Race Mode cannot do, and where it has trade-offs.

6.1 It Consumes More Resources Per Request

Even though Race Mode aims to reduce the total cost per successful project, each race consumes more credits and compute than a single attempt. This is why:

- Race Mode is only available on higher-tier plans.

- Atoms enforces constraints such as:

- Only one active Race Mode per user at a time.

- No use of stateful external tools (e.g., long-lived database sessions) during a race.

- Warnings are displayed when your current credit or resource levels make it unlikely for a race to finish.

When a race cannot start or is stopped due to limits, Atoms explicitly tells you why instead of failing silently.

6.2 Not Every Task Needs A Race

Race Mode makes the most sense when:

- The task is meaningful enough that a failure is expensive.

- The problem space is wide enough that multiple implementations are plausible.

- You are comfortable spending more credits for a higher chance of a strong outcome.

For trivial bug fixes, small copy changes, or quick experiments, the default single-path mode is usually sufficient and more efficient.

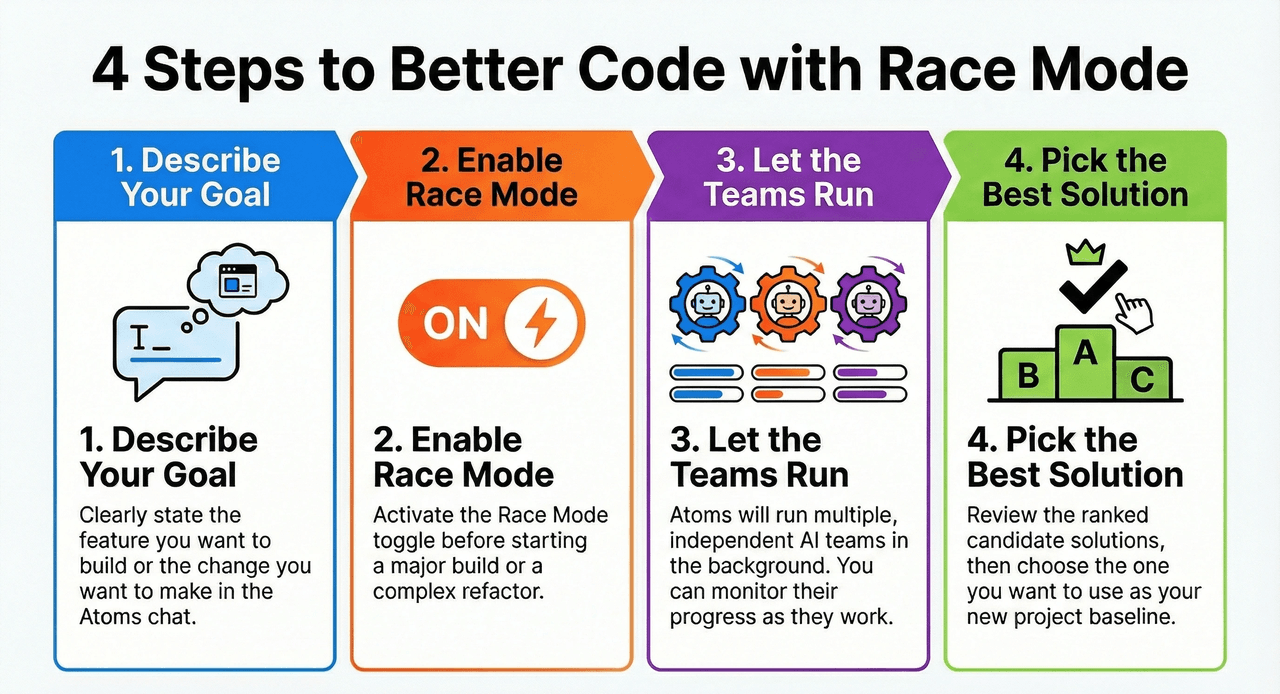

7. Using Race Mode Step by Step

To illustrate this, consider the following typical workflow. The focus is on behavior rather than interface styling, ensuring stability as the UI evolves.

- Describe your goal in Atoms.

- Enable Race Mode before a major build or risky change.

- Let several teams run in parallel; then inspect the resulting candidates.

- Choose one solution as the final project decision.

8. A Note on Style and Transparency

Throughout the design of Race Mode, we have deliberately avoided two common patterns in the AI tooling space:

-

Hiding complexity behind vague language

We explicitly refer to:- Which models participate.

- What benchmarks we use (RealDevWorld, Xbench-DeepResearch).

- How much improvement we see (0.30 → 0.85 on complex tasks; ~45% better effective quality; up to 80% lower cost at a target quality).

- Wherever possible, these numbers come from reproducible evaluations rather than hand-picked anecdotes.

-

Overstating guarantees.

Race Mode helps reduce the role of luck in AI-assisted development. It does not eliminate the need for understanding, review, or testing. The external literature on agents and planning systems points to the same conclusion: more structure and ensembling help, but do not make models infallible (arXiv).

Our intention with Race Mode is to move the default experience closer to how careful teams already use LLMs in high-stakes workflows: multiple attempts, independent reasoning paths, simple automated checks, and deliberate human selection—wrapped into a single, repeatable mechanism.

9. Summary

Race Mode is Atoms’s answer to a concrete problem: single-shot AI development is unreliable, and naïve “just use a stronger model” strategies are expensive. By running several full agent teams in parallel, scoring their outcomes, and helping you select a single solution, Race Mode:

- Raises success rates on realistic, production-style tasks from around 0.30 to 0.85 in our RealDevWorld evaluations.

- Operates along a Pareto-optimal cost–quality frontier, providing around 45% better effective quality at budgets where single-model setups fall short.

- Enables up to 80% cost reduction for a given quality level by selectively using open and proprietary models rather than uniformly applying them.

It does this without adding new buzzwords or pretending to remove all uncertainty. Instead, it systematizes practices, such as best-of-N sampling, verification, and cost-aware model selection, that are already supported by independent research and community experience.

If you are using Atoms to build applications you hope will turn into real businesses rather than demos, Race Mode is the mechanism you can reach for when a feature or refactor is essential enough that “let’s hope the first attempt is good” is no longer acceptable.

Posts

Posts